2024 KalmarCTF

I played KalmarCTF 2024 with my univ club CyKor.

I think we did great considering the number of active members, and there was something to celebrate for myself.

I will write a write-up for challenges I solved/upsolved.

Thanks to everyone on Kalmarunionen for the CTF.

Crypto - Cracking The Casino (69 solves)

The challenge’s goal was to predict the randomness of a commitment.

Dice mode, card mode, and debug mode exist, and debug mode can reveal consecutive random.getrandbits(32) with a very high probability every round. Gather the information 624 times, untemper them, and setting state is enough to predict later outputs.

Solve code: ex.py

I think it’s worth sharing a short conversation about random.randint(0, 2**32 - 2).

Crypto - Re-Cracking The Casino (27 solves)

The previous challenge permitted the user to resign, but this time user has to win 250+ times out of 256, so the previous solution cannot work.

However, if g’s multiplicative order is smaller than h’s multiplicative order, it is possible to get some information about r from commitment.

def commit(pk, m):

q, g, h = pk

r = randint(1,q-1)

comm = pow(g,m,q) * pow(h,r,q)

comm %= q

return comm,r

Setting r’s possible range as small as possible(dice mode) can recover r’s value if g’s order is at least 6 times smaller than h’s order.

It depends on luck setting g, h, so I reconnected like a few hundred times.

Solve code: ex.sage

After reading some discussion after CTF ended, I realized the range check (if not (x > 1 and x < q):) was a bug, which made the challenge slightly more difficult.

def verify(param, c, r, x):

q, g, h = param

if not (x > 1 and x < q):

return False

return c == (pow(g,x,q) * pow(h,r,q)) % q

Crypto - MathGolf-Warmup (32 solves)

The challenge was to generate a normal form from a recurrence relation which looks like this:

Fortunately, I was quite familiar with solving recurrence relations, maybe thanks to Functional(2022 ICC Athens).

However, finding $k$ which makes $s_n + ks_{n - 1} = (a + k)s_{n - 1} + bs_{n - 2} \pmod p$’s both sides the same ratio wasn’t so easy and realized that’s all $p$’s fault.

Fortunately(again, lol), the challenge itself gave a hint about using $\mathbb{F}_{p^2}$, I might have struggled more without it.

Solve code: ex.sage

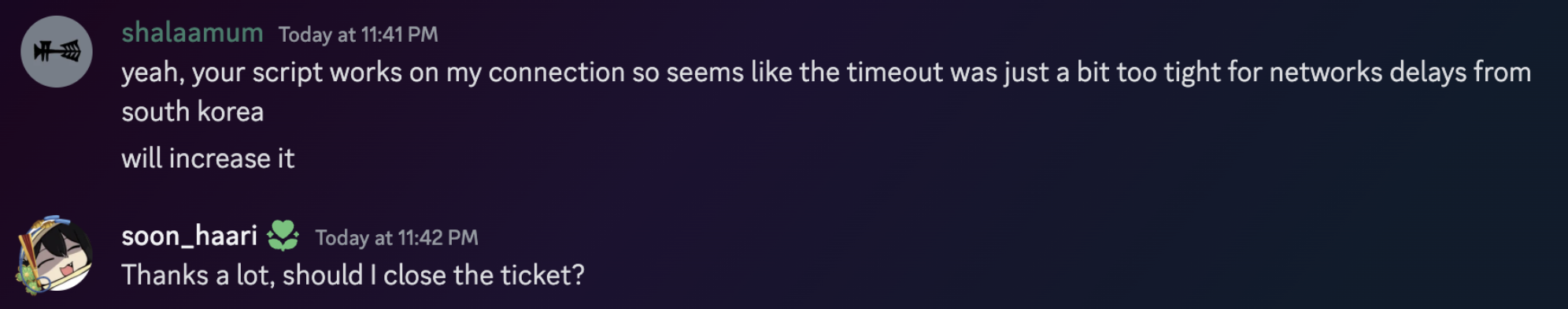

Fun fact: I couldn’t still solve the challenge due to a time limit. The challenge required the user to pass 100 rounds, but with my environment(mostly network packet issues) it was not possible.

However, after making a ticket, the author(shalaamum) handled the issue in the kindest way possible.

(Upsolved) Misc - A Blockchain Challenge (19 solves)

I realized this challenge exists after spending too much time working on 0 solves crypto challs(Which was ****ing worth it), so only 2 hours was allowed for me to solve this.

After very slow code-reading, coming up with a solution didn’t take too long, however after very slow code-writing, minor bugs appeared and I couldn’t manage to finish it within 2 hours.

- Start with some accounts generated, like 10 ~ 20.

- If one of the accounts succeeds in hitting the block, get it, or tick.

- Make sure to generate some more accounts when enough budgets are filled.

After finishing something more important, I fixed the code.

Solve code: ex.py

(Upsolved) Crypto - poLy1305CG (0 solves)

Someone said short-coded crypto challenges are the scariest.

No one including me could solve the challenge during the CTF. And the hint released afterward also didn’t really help me, but at least I got the courage I was in the correct way from it. Turns out my solution was unintended haha.

After solving it, I was so thrilled, that I bought dinner for some colleagues who stayed next to me.

Check it out: x.com

chal.py

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from Crypto.Hash import Poly1305

from Crypto.Cipher import ChaCha20

import os

N = 240

S = 10

L = 3

I = 13

# "Poly1305 is a universal hash family designed by Daniel J. Bernstein for use in cryptography." - wikipedia

def poly1305_hash(data, Key, Nonce):

hsh = Poly1305.new(key=Key, cipher=ChaCha20, nonce=Nonce)

hsh.update(data=data)

return hsh.digest()

# If i just use a hash function instead of a linear function in my LCG, then it should be super secure right?

class PolyCG:

def __init__(self):

self.Key = os.urandom(32)

self.Nonce = os.urandom(8)

self.State = os.urandom(16)

# Oops.

print("init = '" + poly1305_hash(b'init', self.Key, self.Nonce)[:I].hex() + "'")

def next(self):

out = self.State[S:S+L]

self.State = poly1305_hash(self.State, self.Key, self.Nonce)

return out

if __name__ == "__main__":

pcg = PolyCG()

v = []

for i in range(N):

v.append(pcg.next().hex())

print(f'{v = }')

key = b"".join([pcg.next() for _ in range(0, 32, L)])[:32]

cipher = ChaCha20.new(key=key, nonce=b'\0'*8)

flagenc = cipher.encrypt(b"kalmar{}")

print(f"flagenc = '{flagenc.hex()}'")

After surfing the internet a bit, I made a pseudocode of poly1305 hash, and started solving.

from Crypto.Hash import Poly1305

from Crypto.Cipher import ChaCha20

import os

def poly1305_hash(data, key, nonce):

hsh = Poly1305.new(key=key, cipher=ChaCha20, nonce=nonce)

hsh.update(data=data)

return hsh.digest()

def divceil(a, b):

return (a + b - 1) // b

def mypoly1305_hash(data, key, nonce):

rs = ChaCha20.new(key=key, nonce=nonce).encrypt(b'\x00' * 32)

r, s = rs[:16], rs[16:]

r = int.from_bytes(r, "little")

s = int.from_bytes(s, "little")

r &= 0x0ffffffc0ffffffc0ffffffc0fffffff

P = 0x3fffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffb

res = 0

for i in range(0, divceil(len(data), 16)):

block = data[i*16:(i+1)*16] + b'\x01'

res += int.from_bytes(block, "little")

res = (r * res) % P

res += s

res %= 2**128

res = res.to_bytes(16, "little")

return res

for _ in range(10):

msg = os.urandom(os.urandom(1)[0])

key = os.urandom(32)

nonce = os.urandom(8)

res = poly1305_hash(msg, key, nonce)

res2 = mypoly1305_hash(msg, key, nonce)

assert res == res2

1. Setting the goal

Poly1305 works pretty much the same as normal LCG. 128 bit $r, s$ is set initially, and the result is calculated on a modulus $p = 2^{130} - 5$.

In this challenge, in which every hash calculation depended on one block, it can be written as the following:

So we know partial information about LCG’s output consecutively, and there is an attack about it called Stern’s attack(eprint.iacr.org).

I recently learned about this attack thanks to RBTree’s challenge for KAPO(POKA) CTF which was authored by Dreamhack.

So we can conclude we can recover $r$ from outputs’ partial pieces of information with Stern’s attack.

…OR IS IT???

for i in range(0, divceil(len(data), 16)):

block = data[i*16:(i+1)*16] + b'\x01'

res += int.from_bytes(block, "little")

res = (r * res) % P

res += s

res %= 2**128

After calculating the result on $\bmod p$, the hashing algorithm only returns 128 LSB, to make the hash 16 bytes long.

Specifically, $(0 \sim 4) \times 2^{128}$ is subtracted after calculating $ar + s \pmod p$.

We can write it this way:

LCG’s important property is broken, but I will continue and review this when it’s time to use Stern’s attack.

2. Making the unknowns consecutive (Unintended)

We can see hash is represented to bytes with little-endian, and only hash[10:13] is revealed.

So when $k$ is the known 3 bytes of $h$ value, we can write it like this:

Because $p = 2^{130} - 5$, I thought it was possible to make two error variables into one larger error variable by multiplying some.

This is the result after multiplying $2^{26}$.

I will rewrite this in a more general form. $s_i$ represents the small error ($0 \sim 4$) I mentioned in the previous step.

- $h_{i + 1} = a_{i + 1} + 2^{80}k_{i + 1} + 2^{104}b_{i + 1} = rh_i + s - 2^{128}s_i \pmod p$

- $h_{i + 2} = a_{i + 2} + 2^{80}k_{i + 2} + 2^{104}b_{i + 2} = rh_{i + 1} + s - 2^{128}s_{i + 1} \pmod p$

- $h_{i + 1} - h_{i + 2} = (a_{i + 1} - a_{i + 2}) + 2^{80}(k_{i + 1} - k_{i + 2}) + 2^{104}(b_{i + 1} - b_{i + 2})$

- $h_{i + 1} - h_{i + 2} = r(h_i - h_{i + 1}) + 2^{128}(s_{i + 1} - s_{i})$

I will redefine some values.

- $H_i = h_{i} - h_{i + 1}$

- $A_i = a_{i} - a_{i + 1}, (-2^{80} < A_i < 2^{80})$

- $B_i = b_{i} - b_{i + 1}, (-2^{24} < B_i < 2^{24})$

- $S_i = s_{i} - s_{i + 1}, (-4 \leq S_i \leq 4)$

- $K$ represents every known values like $2^{80}(k_{i} - k_{i + 1})$ from now on.

After defining $P_i = 2^{26}H_i, \; t = 5 \times 2^{24}$, the final equations are made.

Now the goal is to recover $r$ from $N - 1 = 239$ infos about $P_i = C_i + K$.

3. Why does Stern’s attack work???

Let’s review Stern’s attack.

Stern’s attack succeeds by finding small vector $\begin{bmatrix} v_0 & v_1 & v_2 & \cdots & v_{d - 1} \end{bmatrix}$ satisfying $D = 0$.

$\begin{bmatrix} P_0 & P_1 & P_2 & \cdots & P_{d - 1} \end{bmatrix}$’s $d$ values are pretty big and random, but there is only one constraint so we can expect vectors with elements’ size around $p^{\frac{1}{d}}$.

What about the current case?

Is it possible for some vector $\begin{bmatrix} v_0 & v_1 & v_2 & \cdots \end{bmatrix}$ to make the upper multiplied result a zero vector?

The result looks like this, and I’m sure you might notice the pattern:

Every term is linearly constructed with $(v_0P_0 + v_1P_1 + v_2P_2 + \cdots)$, and

- $(v_0S_0 + v_1S_1 + v_2S_2 + \cdots)$

- $(v_0S_1 + v_1S_2 + v_2S_3 + \cdots)$

- $(v_0S_2 + v_1S_3 + v_2S_4 + \cdots)$

- $(v_0S_3 + v_1S_4 + v_2S_5 + \cdots)$

- $ \cdots$ .

Unlike $(v_0P_0 + v_1P_1 + v_2P_2 + \cdots)$, making $(v_0S_? + v_1S_? + v_2S_? + \cdots)$ zero is very easy because every $S_i$ is extremely small($-4 \sim 4$)! Even though there are many constraints to satisfy, it is not hard.

In conclusion, we can apply Stern’s attack directly to this challenge too. With well-set parameters, finding working vectors for $\begin{bmatrix} v_0 & v_1 & v_2 & \cdots \end{bmatrix}$ isn’t very hard. We finally can calculate $r$.

4. The rest of the challenge

From 13 lower bytes of $hash(“init”)$, we can recover lower 104 bits of $s$. We can write $s = 2^{104}s_a + s_0$ and also can represent the initial state with $s_a$ after some observation.

There are only $2^{24}$ possibilities for $s_a$, so brute-forcing until LCGs are in good shape and decryption results in a good-looking flag can solve the challenge.

Thanks to Lance Roy for the challenge.

My super dirty solve code: ex.sage

- My solution is unintended, it will be awesome to study the Author’s solution too.

- Special thanks to Genni, I rearranged my solution yesterday while talking with him. He thinks every column sharing the same constraints isn’t so magical after understanding. :(